An East End

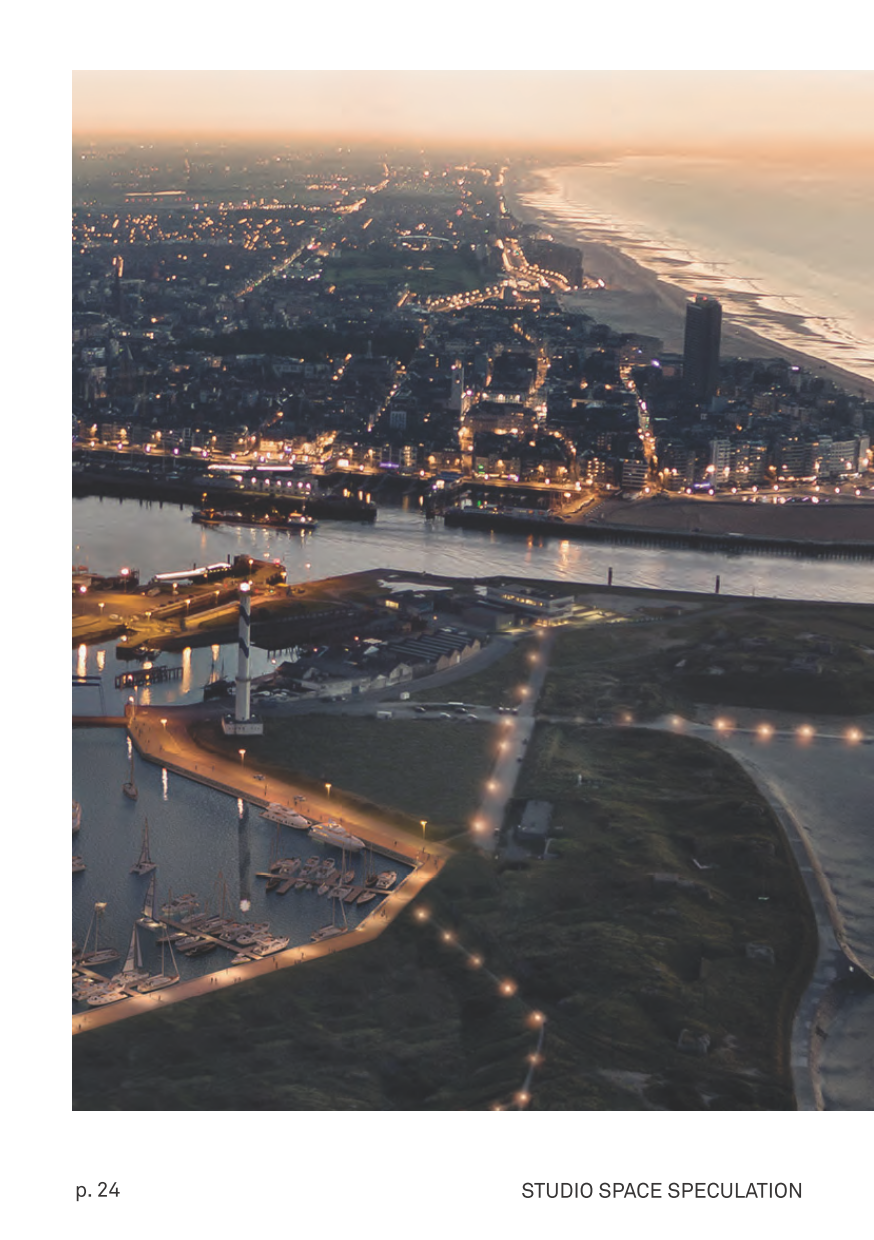

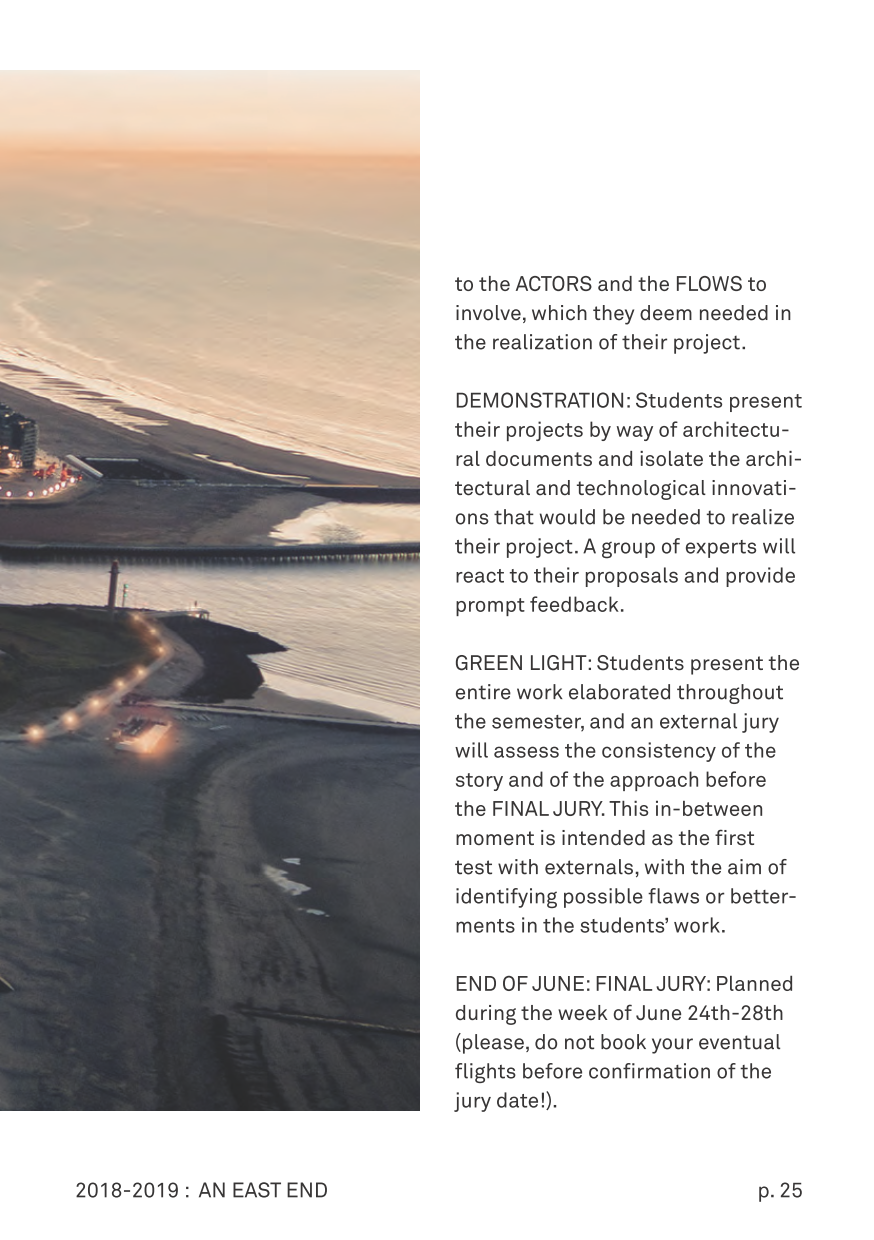

We dive into the Port of Ostend this semester, located at the North Sea and at the mouth of the canal linking it to Bruges and beyond, to an essential economic and logistical network of players. Once the point of arrival and trading of Belgian fisheries, serving an important market and processing industry stretching over the whole North-Western European region (from Amsterdam to Koln to Luxembourg), the port has seen this activity mostly substituted by the assembling of the wind turbines that populate the offshore wind park. As many port areas, part of its old industrial waterfront has been redeveloped for housing (e.g., Baelskaai at Oosteroever), which means that any future project will have to meet the conflicting demands (housing and working areas, and recreation and nature development) characterizing these mixed-use districts. The current port of Ostend was created following the man-made piercing of the dunes with a gully (Oostegeul) in the third quarter of the 15th century. This gully was built as part of a military strategy to prevent guns and canons from being positioned on those dunes and oriented towards the walled city. The result was an artificial inundation of the area, of a scale that was entirely unexpected, caused by the violent tidal activity of the sea during part of the 14th and 16th centuries. The eastern side of the city became a landscape of creeks - with the Keignaard creek later becoming the new bed for the construction of the canal to Bruges. After the gradual reclamation of the gully’s flooding area, the Ostend polders were created, used formerly as sluice polders for the port until the first quarter of the 19th century. All those works forcing nature into an engineered corset always had a military and strategic role, and the expansion of the city was forever paired with these military purposes. This trend was only reversed with the declaration of independence in 1830. Only then could Ostend grow into a unique place as a trading and fishing city first, and as a fashionable seaside resort and a royal residence of Leopold I when the Bruges-Ostend rail link (1838) was built.

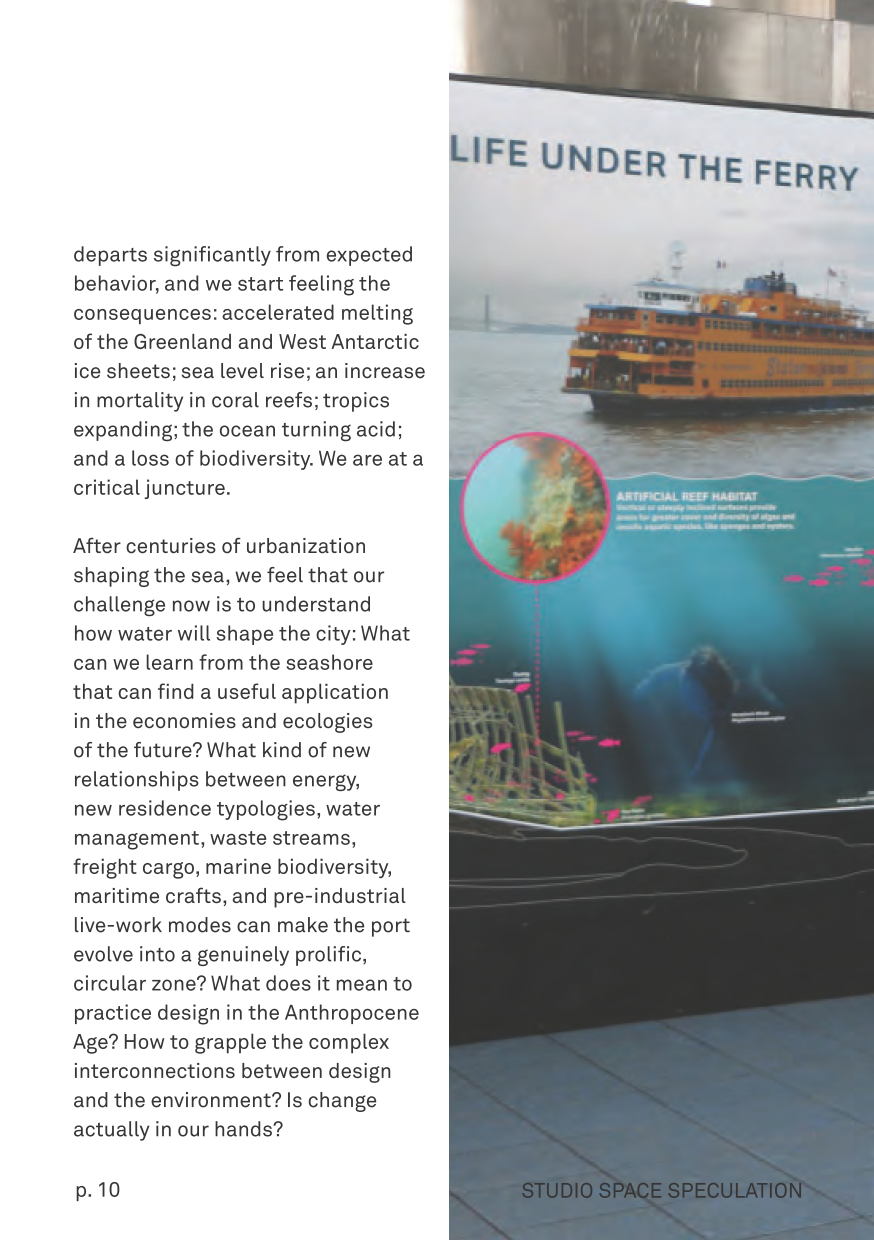

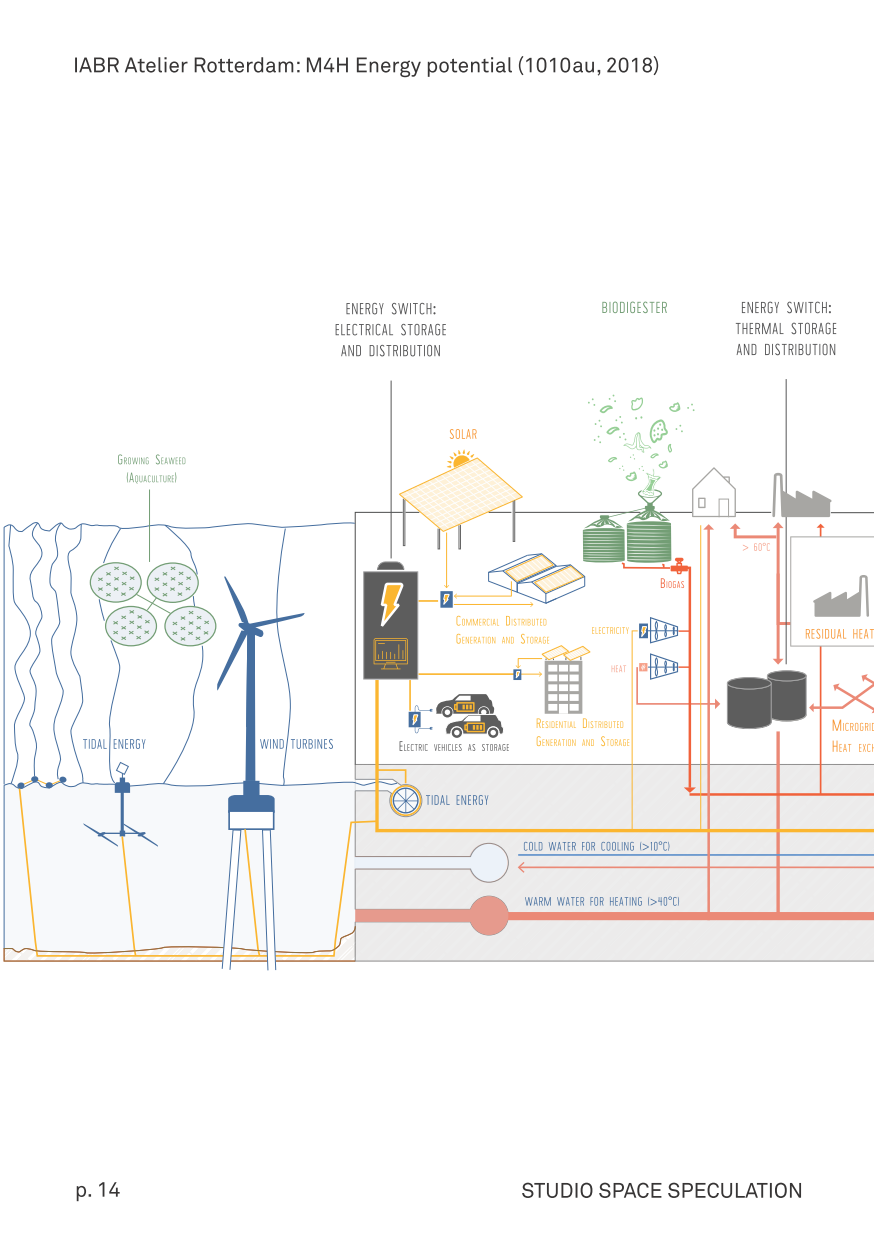

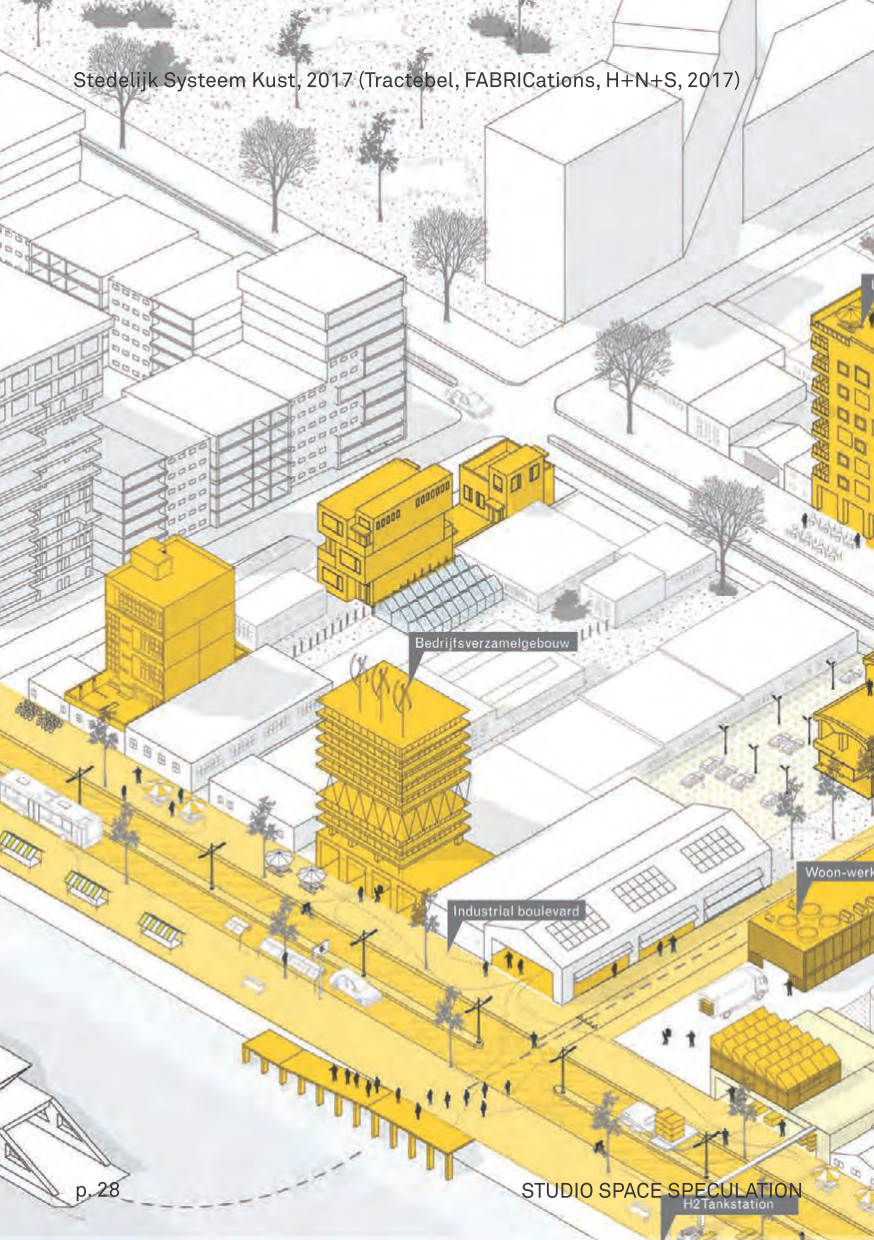

Nowadays, the port is compartmented into a tidal port, where the sea enters freely, and a non-tidal port, which is closed by locks. The average low water is TAW + 0.39 m, the high water is TAW + 4.28 m. The total water surface is approximately 115 ha, and the whole bank length 11,000 m. The industrial area is about 300 ha big and accommodates port-related industry (stevedores, transshipment companies), logistics, chemical industry, fishing-related companies, the navy and, since recently, the REBO (Renewable Energy Base Ostend, for the offshore platforms). There is a large Spuikom to the south-east of the harbor. The east end of Ostend is a space of mediation between the sea and the land, and between the dunes and the polder. It all started with the creation of new land out of marsh and sea between the 10th and the 12th century: the systematic embankment and the erection of permanent dikes allowed settlements to move from higher grounds to the coastal floodplain. Because of the extremely dynamic nature of the North Sea coastal system, this first urbanization of the seashore was put permanently under thread, witnessing several episodes of radical change since the initial reclamation in the High Middle Ages. Above all, the sometimes catastrophic storm surges helped to demonstrate the degree of fragility that characterized these man-made landscapes, at least up to the 18th century, when new hydraulic inventions were implemented. The east end is physically located at the seashore, a limit between the land and the sea, and discursively situated at the limits of our planet, in the sense that this planet has become too small to metabolize human activity and come out untouched from it. The idea that humans could fundamentally alter the earth is new, let alone that humankind would induce a new geological era called the Anthropocene (Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, 2000). As the climate warms and CO2 concentration increases, climate departs significantly from expected behavior, and we start feeling the consequences: accelerated melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets; sea level rise; an increase in mortality in coral reefs; tropics expanding; the ocean turning acid; and a loss of biodiversity. We are at a critical juncture. After centuries of urbanization shaping the sea, we feel that our challenge now is to understand how water will shape the city: What can we learn from the seashore that can find a useful application in the economies and ecologies of the future? What kind of new relationships between energy, new residence typologies, water management, waste streams, freight cargo, marine biodiversity, maritime crafts, and pre-industrial live-work modes can make the port evolve into a genuinely prolific, circular zone? What does it mean to practice design in the Anthropocene Age? How to grapple the complex interconnections between design and the environment? Is change actually in our hands?